My Site - Your Local Business Hub

November 7, 2024 – January 31, 2025 | Monday to Friday, 11 AM to 7 PM; Saturday, 11 AM to 3 PM; closed on Sundays.

This show, centered on the concept of metamorphosis in indigenous, popular, and contemporary art, will feature works by Tunga, Salmi Lopez, Nuno Ramos, Jandyra Waters, Manuel and Francisco Graciano, José Bezerra, Véio, Artur Pereira, among others.

Vilma Eid

As 2024 comes to a close, we at Galeria Estação will always remember this year with joy: it marks our twenty years in the business!

Did it go by quickly? For those looking from the outside, perhaps. For us, it has been a time filled with learning and achievements! We’ve faced challenges and conflicts, but above all, we’ve gained recognition and prominence in the ever-competitive art market. This has been possible thanks to the journey we've taken alongside my partner from the very beginning, Roberto Eid Philipp, and our entire team.

2024 has also been special for me! I celebrated forty years as a gallerist and published Moderno / Contemporâneo / Popular / Brasileiro – O olhar de Vilma Eid with WMF Martins Fontes, which chronicles my journey and showcases my personal collection and Galeria Estação.

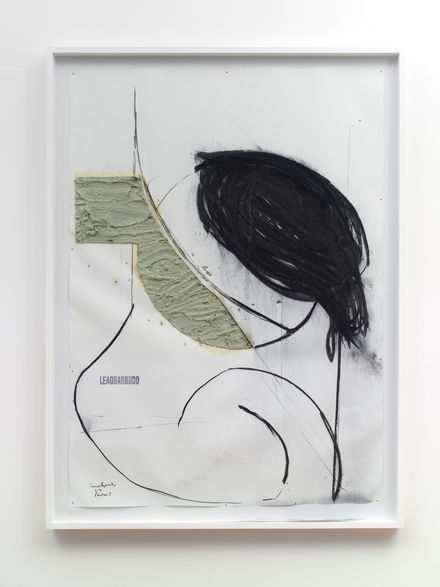

And there’s more. As we close the year, we are opening the exhibition Metamorphoses & distances. This show, centered on the concept of metamorphosis in indigenous, popular, and contemporary art, will feature works by Tunga, Salmi Lopez, Nuno Ramos, Jandyra Waters, Manuel and Francisco Graciano, José Bezerra, Véio, Artur Pereira, among others.

A heartfelt thank you to our invited curator, friend, and companion throughout these twenty years, Lorenzo Mammì.

VILMA EID

LORENZO MAMMÌ

METAMORPHOSES AND DISTANCES

This exhibition explores two constants in Brazilian art, not just in popular art: the transformation or instability of forms, and the distance, in two senses: as detachment or estrangement from the represented space, and as the construction of centripetal, closed forms that isolate themselves from the space in which they are placed. These are not two distinct characteristics, as if each artwork could belong solely to one of them. In many cases, they coexist simultaneously, in a dialectical tension. However, the opposition between them seemed useful for addressing a material with such varied origins and outcomes in a transversal way. Fluid forms, transitions, and ambiguities are constants in Brazilian art, especially after the concretist phase. Rather than assertive forms, many artists favor unstable configurations that suggest the passage from one form to another. An established reading posits that this reflects a not fully formed condition of our art system and public space. This is plausible. Yet recent anthropological literature, pointing to the fluidity of distinctions among species in Indigenous cultures and the "structural inconstancy of the 'wild soul'" (Viveiros de Castro), may suggest another reading—not opposing, but complementary: perhaps the preference for processes of transformation is not only a creative response to the fragility of artistic institutions but also the emergence, in times of crisis, of a more ancient imaginary. If this is true, the so-called popular art, produced in Brazil outside of the Academies and meeting the needs of the majority since the colonial period, will be a privileged ground for investigation: it is where the essence of a common culture is formed. The reference to Indigenous culture is explicitly evident in the fantastical zoology of Chico da Silva from the same region. But thousands of kilometers away in Paraguay, Salmi Lopez, of the Ishir ethnicity, also describes interspecies relationships: in his drawings, supplemented by explanatory texts, shamans descended from a mother fish transform into birds that fight in the sky. Sometimes the derivation from Indigenous culture is not so direct, yet the kinship seems undeniable. Manoel and Francisco Graciano (father and son, from Ceará) are masters of metamorphosis: they explore the contours and veins of tree trunks to create composite beings, intricately intertwined. Even a sculptor known for more compact and polished forms, like Artur Pereira, suggests a symbiosis among human figures, animals, and trees in his series Caçadas (Hunts). Finally, in the works of Véio and José Bezerra, it is the wood itself that seems to transform, taking on animal or human life, while the artist merely accompanies the process with discreet interventions. In Western thought, indeterminacy is not a potential for dialogue among species but a threat of indistinction that must be kept in check. Its exemplary figure is Proteus, the god of transformation whom Odysseus binds to force him to reveal the truth. But Proteus’s truth is not that of Odysseus. It reveals itself in the instability of materials and beings, which Tunga explores in both the alchemical drawings of La Voie humide and his latest three-dimensional series, Morfologias (Morphologies). Nuno Ramos dedicated a series of drawings (two of which are in this exhibition) to Proteus’s truth, where a very simple formal scheme (two straight lines and two curves) becomes contaminated by gestures and contact with the material of pigments. A more mysterious and subtle fusion is found in Jandyra Waters, who produced non-geometric abstract canvases in the 1960s, which are not informal either, full of zoomorphic suggestions. Waters was closely associated with the psychoanalyst, critic, and collector Theon Spanudis, who at the time advocated for an abstraction that extended beyond rational organization of forms to embrace the imaginary (perhaps with slight surrealist influence) and aspired to transcendence. The second part of the exhibition, dedicated to "distances," is more composite. Strictly speaking, the concept of “distance” primarily applies to the series of landscapes on display here. In all of them, there is a sense of detachment, almost of exile—a form of alienation from the place, an impossibility of belonging. This is not limited to popular art: great erudite Brazilian painters evoke the same feeling: Guignard, Pancetti, Koch—all with good reasons to feel foreign in their homeland. Moreover, Cardosinho, present here with six paintings, is not exactly a popular painter: a Portuguese who studied philosophy and taught Latin and French in school, he only began painting after retiring in 1931, at the age of seventy. It’s as if he were a 19th-century man gazing at modern art (which he knew from his associations with Portinari and Foujita and from participating in major artistic events, starting with the Revolutionary Salon of 1931) through a window—or rather, through newspaper pages and the postcards he meticulously reproduced, sometimes even adhering to the black and white of the photographs. The almost metaphysical suspension characterizing Cardosinho’s canvases echoes another form of strangeness, that of Júlio Martins’s landscapes—who, in contrast, is a typically carioca figure: bohemian, carnival-loving, without a steady job until he became a cook at the Hotel Avenida. Yet his paintings depict another place, viewed from afar and above, with wealthy palaces surrounded by well-tended gardens, where elegantly diminutive figures stroll among statues that gesture more than they do. Everything is mediated by soft colors, predominantly soothing shades of green. It’s almost the exact reverse of Cardosinho: a 19th century imagined by a man of the 20th century. In this setting, each element becomes isolated, as if it were more named than seen. The internal division is more pronounced in Neves Torres. He paints another world, but this one truly existed: a tractor driver for most of his life and a painter only in old age, like Cardosinho, Neves Torres once owned a small farm, and it is from this place that his paintings speak. His works are divided into juxtaposed areas, each containing a detail: men and women working or resting, crops, animals—as if the painter extracted them one by one from memory. Yet sometimes, with slight modifications, these patchwork areas of color become creatures or monsters. Another, more unsettling narrative emerges from behind the bucolic scene. A toothy mouth threatens the man resting in a hammock; another man, by the pond, has his body transformed into a table. The metamorphic factor, which threatens the organized world, justifies the inclusion of some of Neves Torres’s paintings in the first section of the exhibition. The tension between compartmentalization and transformation is far more dramatic in Aurelino. Here, the orthogonal layout of the canvas, often reminiscent of his city (Salvador) viewed in plan or section, attempts to contain the uncontrolled proliferation of images. This is how Prinzhorn described the paintings of schizophrenics in the early 20th century: a rigid categorical structure desperately trying to organize an extremely unstable visual material. In Aurelino’s case, the effort to contain results in some figures, pressed by the outlines, becoming rigid in a hieratic posture that surprisingly echoes the reflective and self-aware art of Agnaldo dos Santos. More than referencing Afro-Brazilian art, Agnaldo’s sculptures connect to African art, which he encountered mainly through Pierre Verger. We are now in another realm, described by anthropologists like Philippe Descola as totemic, in contrast to Indigenous animism. The image embodies an ancestral quality that is preserved by being a closed, impenetrable, and compact body. Even the heads of Conceição dos Bugres, while evidently Indigenous, possess this totemic character. The technique of yellow wax coating, learned by Conceição in a dream, accentuates this isolation. The same sacredness emanates from Dona Isabel’s ceramics: her women, styled and dressed in modern attire, nonetheless retain the solemnity of a totem. Originally, they were water jugs, repositories of precious water. But from Neves Torres’s paintings, we can also draw another thread: the organization of juxtaposed areas resembles the sculptures of Nino, who also uses isolated figures against varied colored backgrounds, creating a surprising mix of three-dimensional sculpture and bas-relief. Also from Ceará, Nino is almost a complementary opposite of the Gracianos: in their work, figures do not merge; in his, they relate from a distance, like elements of a riddle. Here, another technique stands out: enumeration. In Nino’s work, it still involves the association of distinct figures, each with its own characteristics. The unity is narrative, like different episodes of a fable. However, it may involve the same figures repeated, sometimes in different positions, unified by belonging to the same block of wood or inscribed in geometric shapes, as seen in Artur Pereira’s nativity scenes or G.T.O.’s “living wheels.” In Alcides’s work, however, repetition includes a disruptive factor. A Bahian who initially settled in Mato Grosso and later (since 1992) in São Paulo, Alcides initially painted bucolic scenes with delicate decorativeness. The impact of modernization begins to reveal itself in works like Presidente Castelo Highway and Woodcut, where the geometric shapes and flat colors of trucks, warehouses, and roads violently disrupt the serene rhythm of natural environments. It explodes in The Landscapes/The Coconuts, painted in São Paulo. In this canvas, the oval figures against a green background, containing irregular white patches, may represent open coconuts. The rest is organized in rows: a line of hay bales at the bottom, followed by a line of pots and another of various handcrafted items, arranged as if for a roadside sale; a couple seated on two benches, separated by a line of grass; and finally, on either side of the coconuts, four large oval forms that may represent flowering trees, yet also resemble the pots in the lower row. The meticulous enumeration of objects and the relative symmetry of the composition do not conceal the threat of imminent chaos, of a rural world on the brink of losing its meaning. It is, literally, a world in tatters. Félix Farfan is an urban artist. He feels at home in the multiplication of stimuli, in the proliferation of disposable objects, in the intersecting web of information that thickens until, as Robert Smithson said, it becomes a compact shell upon which one can run. He clearly has one foot in underground culture, deriving from it a taste, of Eastern origin, for the analogical relationships between microcosm and macrocosm. But everything is inscribed in the closed circle of a system that reproduces itself to the point of vertigo: in this perspective, the human body objectifies itself in anatomical boards; the universe is encompassed in the totality of products that mass culture offers. The exhibition also includes a sculpture by Elisa Bracher. Due to its centripetal force, where tension is generated internally, at the point where a log or stone rests on another, many of Bracher’s works can be likened to totemic forms. However, in this particular piece, and others from the same series, the blocks of wood house small niches containing clay houses: it is as if the closed body of the totem embeds the landscape. This sculpture particularly evokes the vertical landscapes of China, with their small dwellings nestled among rocks separated by clouds; or those of Guignard, whose proximity to Chinese art has often been noted. Yet the vapors have become solid; distance, a tangible presence. The strangeness remains a guarded treasure. Lorenzo Mammì Curator

.jpg)

"If this is true, the so-called popular art, produced in Brazil outside of the Academies and meeting the needs of the majority since the colonial period, will be a privileged ground for investigation: it is where the essence of a common culture is formed."

Lorenzo Mammì, curator.

Metamorphoses and Distances

When: November 7, 2024 – January 31, 2025

Where: Galeria Estação

Address: Rua Ferreira Araújo, 625 - Pinheiros, São Paulo

Gallery Hours: Monday to Friday, 11 AM to 7 PM; Saturday, 11 AM to 3 PM; closed on Sundays.

Phone: 11 3813-7253

Email: contato@galeriaestacao.com.br

Website: www.galeriaestacao.com.br

Instagram: @galeriaestacao

Directors

Vilma Eid

Roberto Eid Philipp

Curator

Lorenzo Mammì

Texts

Lorenzo Mammì

Vilma Eid

Commercial Director

Giselli Gumiero

Sales

Amanda Clozel

Matheus dos Reis

Production

Lu Mugayar

Marketing Director

Luciana Baptista Philipp

Communication

Zion Digital Marketing

Photos

Filipe Berndt / João Liberato / Germana Monte-Mor / Rodrigo Casagrande / Lucas Cruz / Gabi Carrera / Bruno Leão / Eduardo Ortega

Editing

Cadu Pimentel

Lighting and Production Support

Marcos Vinícius dos Santos

Kléber José Azevedo

Press Office

Baobá Comunicação, Cultura e Conteúdo

Proofreading

Otacílio Nunes

Translation into English

Maria Fernanda Mazzuco - Inglês

Impressão e acabamento

Romus Indústria GráficaElisa Bracher

Acknowledgment

Elisa Bracher

Galeria Fortes D'Aloia & Gabriel

Galeria Millan

Instituto Tunga

Nuno Ramos